Hal Cannon writes about a recent visit to Ella Gant McBride, who was recorded by John Lomax in the 1930s singing with her family in Austin, Texas. I felt guilty recently as I drove south from Salt Lake City to Santaquin, Utah, to visit Ella Gant McBride. Years ago, Bess Lomax Hawes had told me about the Gant Family. Beth came from a long line of folklorists: her father, John A. Lomax, had recorded rare folk songs from the Gants in the mid-1930s when they all lived in Austin, Texas. The Gants were Mormon, and Bess knew I’d grown up in Utah. She thought I should follow up, but I’d taken my sweet time.

John Lomax recalls visiting the Gants in 1934 on a weekday, late in the morning. It was so quiet he almost left the house. Finally a woman answered the door in her bedclothes. Yawning, she whispered “Last night we all got to singing and dancing. We didn't go to bed until 2 in the morning," Eight children were still asleep and their mother, Maggie Gant, was staving off the Great Depression the only way she knew how. As Lomax reported in his 1941 book, Our Singing Country, she told him that “the singing kept us so happy, we couldn’t go to sleep.”

Bess remembered meeting the Gants when she was a young girl. While her father recorded the adults in the family’s shanty on the banks of the Colorado River in Austin, Bess and the younger Gant girls, Foy and Ella, hid out under the porch telling stories to each other and listening to the music that drifted down through the floorboards. Mike Seeger, who incorporated songs from these early field recordings into the repertoire of his group, the New Lost City Ramblers, liked to talk about “true vine,” the music that grew organically through family, occupation and community to be passed on through generations and occasionally shared with outsiders who cared enough to search it out. This image, of John Lomax and the rest of the family in the living room singing while the girls whispered and giggled below rooted by their own interests, brings the concept to life.

I played music with Mike just a year ago. He was one of my mentors and is gone now. John Lomax died in 1948, the year I was born. All of John Lomax’s children have passed on including Bess. And of all the Gant family that Lomax recorded, Ella is the only one left, sitting in a place called the Latter Day Assisted Living Center 60 miles south of Salt Lake City. As I drove down the highway I began singing one of those songs that Mike Seeger learned from the Gants, a song that many people have covered over the years including Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Jerry Garcia.

When first unto this country, A stranger I came I courted a fair maid, And Nancy was her name I courted her for love, Her love I didn't obtain Do you think I've any reason, Or right to complain

Earlier, Ella’s son Wayne had told me repeatedly not to expect too much. I didn’t think I’d gone with expectations. I wanted to meet someone who had actually been recorded by John Lomax. I brought a CD copy of a few of the songs from the Library of Congress that Ella had recorded with her sister Foy when they were just girls. I fantasized that Ella would hear her girlhood voice and start singing along with those recordings. I would record this blending of the old lady and girl and my guilt would be assuaged. In addition, I’d get some good tape for our radio story about John Lomax.

The moment I walked into Ella’s room I realized I would not be recording anything that day. Ella had barely a whisper left as she sat in her recliner clutching a blanket, her eyes opening halfway to talk to me. I asked if she remembered the time under the porch with Bess and Foy and she answered yes. Then she asked me if I liked her. I answered yes. She opened her eyes a little and looked at me, saying in her faint voice, “I love you.” I asked if she still remembered the old songs from her family. Again, she said yes. I told her I had brought some recordings of her singing and asked if she would like to hear them. Again, “yes.” I put the CD in her bedside player and listened as the scratchy sound of the original 1935 acetate disk began to play. The recording started with the archivist saying, “AFS 64, A side.” He set the tone arm on the ancient disc three times before it would track from the beginning and then the music began—two sweet untrained voices, singing in unison.

My Love’s a jolly cowboy, he’s brave, he’s kind, he’s true, He rides a Spanish pony and throws a lasso, too. And when he comes to see me, our vows we do redeem He throws his arms around me and then begins to sing

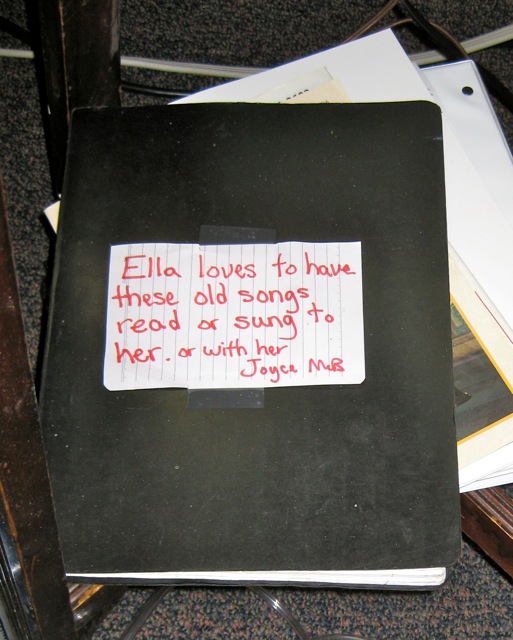

I could tell Ella was listening, recognizing the song. Just then, I noticed a homemade binder under her bedside table. A piece of paper was pasted on the cover, which read: “Ella loves to have these old songs read or sung to her.” I opened the binder. On the first page was a telling inscription: “dedicated to my eternal husband Mark.” Following were pages of family photos and a sheet talking about the importance of keeping and preserving family songs. Then came the collection itself, at least a hundred songs, both words and music all compiled by Ella. I knew many of them as old ballads from Great Britain, popular songs from the Civil War era, cowboy songs, sentimental songs from the day and original songs Ella had written. When she was compiling the book she consulted her family for the accuracy of lyrics and it brought them together. It started to dawn on me that Ella was the very last of this singing family who knew the joy of music mixed with the bitterness of hard times. These songs were at her core.

I could tell Ella was listening, recognizing the song. Just then, I noticed a homemade binder under her bedside table. A piece of paper was pasted on the cover, which read: “Ella loves to have these old songs read or sung to her.” I opened the binder. On the first page was a telling inscription: “dedicated to my eternal husband Mark.” Following were pages of family photos and a sheet talking about the importance of keeping and preserving family songs. Then came the collection itself, at least a hundred songs, both words and music all compiled by Ella. I knew many of them as old ballads from Great Britain, popular songs from the Civil War era, cowboy songs, sentimental songs from the day and original songs Ella had written. When she was compiling the book she consulted her family for the accuracy of lyrics and it brought them together. It started to dawn on me that Ella was the very last of this singing family who knew the joy of music mixed with the bitterness of hard times. These songs were at her core.

I turned off the first recording and asked her if she remembered the song. She said, “Oh yes.” Then she looked at me again and said, “I love you.” This time I don’t think she was talking to me. Maybe she was speaking to Mark, her eternal husband. She began to cry, “I love you so much. I love you so much.” She held out her hand and I took it. In her hand there was such love. It seemed for a moment that all that was left of Ella Gant McBride was a shell of a body, some scattered memories, and a clear deep abiding love, pure love. At that moment it didn’t matter that I was not the love of her life she was talking to. I was simply the conduit for her love.

I’ve thought a lot about interviewing, and have interviewed people all my life. The great practitioners approach interviewing with a variety of values. Some think it is all about listening. Others keep a critical mind and make an interview into a game of outfoxing the other. For me it is all about empathy, trying not just to listen but to feel what the other person is feeling. I’d never tried to interview someone with dementia before. With Ella I sought to feel what she felt as she listened to the songs. I’d never known her before today so I could not compare her to the way she was. I was there without judgment. In a way, meeting Ella for the first time was like joining her in her dreams. She did not have much language or voice left to express herself but she had feeling, strong feeling, and that feeling was love. We listened to the next song both sitting silently.

When I was a little boy, fat as I could roll When I was a little boy, fat as I could roll Sent me on a bus and then we had a show

Listen to Ella and her sister Foy sing "LongCameJohnny." Courtesy of the American Folklife Center, Library of Congress.

[audio http://westernfolklifecenter.files.wordpress.com/2010/05/longcamejohnny3.mp3]

After it ended I said, “Isn’t it amazing, 75 years later, we can still hear you and your sister singing? You were just girls. Do you remember singing with Foy?” This time she said, “Foy was my sister. I love her so much. Foy, I love you so much, I love you Foy.” Again, she started crying. It was almost as though Ella was calling out to Foy on the other side, calling for her sister to find her. I had come to express my gratitude to Ella for the Gant Family songs, but now I began to feel uncomfortable being a stranger in this very personal place. I told her I thought I better leave. She took my hand again: “Please don’t leave, stay a little longer.”

So, having no questions, no answers, I put on another song.

No more have I a mother’s love No more have I a father too No more have I a mother’s love

We sat and listened and I could tell she was taking it all in. Now it really was time to leave. I told her next time I’d bring my guitar. She said, “Good, I’d like that.” She asked for my hand and again told me she loved me. She took my hand to her lips and kissed it tenderly, then looked up and said, “I just want to die, I need to die.” I answered that I understood… and I do.

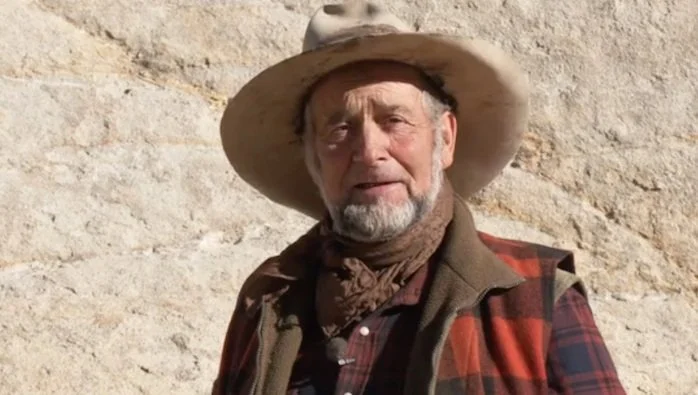

Hal Cannon

Read more about the Gant Family in a recent article by Michael Corcoran in the Austin American Statesman.

Ella Gant McBride passed away peacefully on the day after this blog was posted, May 19, 2010.