Got a Question? Ask A COWBOY POET!

March 2024

When and how much do cowboy poets stretch a story? Where does historical fact lie in a supple oral tradition? The poets stress the finer points of “dancing lightly ’round the truth” as they answer this month’s two-part question:

“Artistic license” has undoubtedly been exercised in many legendary poems and stories that have been passed down through our oral tradition. Could you comment on how you approach decisions about taking artistic license in your writing? Also, could you comment on any historical poems you’ve researched where you’ve found the legend has outpaced the truth or the truth is in fact stranger than fiction?

~The Man Who Didn’t Shoot Liberty Valance

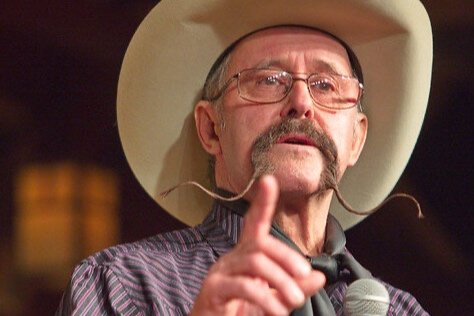

waddie mitchell:

The definition of artistic or poetic license is pretty much wide open. We all use it to some degree to give our mind solace for the manipulation and borrowing of idea, word, circumstance, character, etc. It has been said, "you never want the truth to get in the way of a good story." If you think about it though, it would be near impossible to write almost anything that hasn't been written before. When the first human painted/wrote of his wild hunting adventure on cave walls, many followed with their hunting stories. Stories from each continent throughout all time have been lived over and over. How many love songs have been written? How many war stories?

In reality, there are only so many emotions, circumstances, and experiences the human race can relate to. A lot to us, not so much in the bigger scheme. We show up here on Earth and breathe, drink, eat, hurt, find pleasure, laugh, love, cry, learn, and a bunch of other things, but none of that is unique to us.

We have unique (to us) ideas, unique (to us) adventures, etc., but there have been countless souls before us who did the same.

So, poetic and artistic license has been used, is being used, and will be used as long as man walks this planet and writes their stories.

I've written story poems of things that happened to me and stayed true to the facts. I find that seldom works. A few little detours and change of situations can make the story memorable. I figure the more license I use the more memorable my stuff will be.

dick gibford:

In my opinion, we would not be blessed with such a wonderful collection of songs and poetry if us writers were too concerned about taking artistic license. Of course, we take artistic license as writers in just about everything. Except for historical poems. My favorite poem that is historical was written by Longfellow, “Paul Revere’s Ride,” and the day, month, and year of the event was carefully placed in the start of the poem by old Henry. ‘Twas “the 18th of April, in ’75.” It is one of my favorites and I love to recite it! I am not sure what else to say in regards to this question. In writing cowboy poetry, the author needs to be free in the spirit of the wild and woolly West, most times, to be able to capture the feeling. I say, “Powder River, Let ’Er Buck!”

YVONNE HOLLENBECK:

I’m not a student of classic poetry and write most of my poetry at random based on everyday happenings on the ranch or regarding my lifestyle. With that said, I have been known to take artistic license with the words to old songs, such as “I’d Like To Be in Texas For the Roundup in the Spring.” I wrote a poem about why I’d like to be in Texas when we round up in the spring, and it explains the work this old gal gets involved with at roundup time, and it’s a far cry from that described in the song. I’ve also written a poem dispelling the myth that Santa Claus is a man, rather I believe Santa is a woman, and why.

bill lowman:

First off, I'm not sure that I've ever applied for an "artistic license." I try hard to tell it like it is and not embellish the truth. I'm a contemporary poet. My musings are to record and preserve our current cowboy culture of events that I've been involved in or a witness to. This also applies to my visual arts. I don't write a poem or story or do a sketch unless there's an incident or happening extraordinary enough that it should be preserved for history.

Part two: As a lifelong dyslexic with a severe reading disability, my research of historic poems comes from oral presentations by colleagues. "Tying a Knot in the Devil's Tail" first comes to mind as a poem "stretching the truth" to get a point across.

The great old classic "Lasca" has a line in it that's debatable, when the fiery little señorita stabbed him—"But, I soon forgave her, for scratches don't count in Texas, down by the Rio Grande." It's a great line that gets a point across, one that first comes to mind whenever that poem is mentioned. I've never known a stab wound to be a scratch. That's like Bill Clinton trying to redefine "IS."

annie mackenzie:

Most of my poems are factual. I love being able to answer the question, "Did that really happen?" with, "Every line of it." The only one that I can think of off the top of my head that's not entirely accurate is “A Serious Cowman,” which is about my dad and his cats, and even it's not much of a stretch. He really does love those furry little bastards!

dw groethe:

I really like this question. When it comes to writing down a little happenstance event and making it a poem, it never hurts to dress it up a bit. The whole point to the piece is to keep the attention of the reader or the listener. This ain't the 5 o'clock news; this is entertainment. If it's a serious poem, then you'll want to use imagery that sets the tone right and that will more likely contain thoughts or things that never occurred but are needed to bring the right feel to the story line. Lighter poems are absolutely notorious for having an elastic way with the truth. So, when it comes to "artistic license," I think the best rule of thumb is to never stray too far from your basic inspiration for the poem but still do whatever it takes to make the piece fun. And as always...less is more...so don't overload a poem with bits that you might like but that don't add anything to the story.

Folks are smart enough to know that it's probably not a history lesson they're getting but a mighty fine version of it nevertheless.

Pat Richardson had a short four-liner that summed it up perfectly, but I'm darned if I can find my copy. It basically says...nothing entertains the youth like "a cowboy dancing lightly 'round the truth."

Hope that helps you. Thanks for asking.

Ta daa,

d dub