Got a Question? Ask a Cowboy Poet!

July 2023

We’re turning the tables with a poet’s-choice question. This month, what was one question became many when the cowboy poets were asked what they want to be asked! Buckle in for a lot of hows, wheres, and whys...a good smattering of becauses…and the goings-on in the poets’ minds on both sides of a question. To riff off Waddie’s words, it’s a question “because of” and “for” the cowboy poet. And, while the asker is anonymous, we can tell you the inquiry came from that strange, ever-curious and mostly courteous, breed…a folklorist.

What question would you like to be asked?

–Curious but Courteous

Bill Lowman:

I’ll answer most any question…but there is one that I wouldn’t. “How many cows do you have?”

That's an odd question. I'll answer most any question, I don't have a favorite, but there is one that I wouldn't. We have many, many acquaintances and friends that are not of our culture, many are guests at our ranch. I've always made it a point to ask and listen to their way of life, as they in turn do the same. Although, out of curiosity and politeness, they will just about invariably ask, "How many cows do you have?" That's a question ranchers won't answer. It's like asking us how much money we make in a year. We don't ask them what their annual salary is. It's not meant to be nosy, but it's nobody else’s business besides our banker and us.

Wally McRae hit it on the nose with a poem he wrote years ago. It's in one of his published books that I have. I don't have it in front of me now, but the closing verse tells it all. I won't have it word for word, but the message is the same. It goes something like, "You can ask me any question and I'll answer like a shot, ’cept don't ever ask me how many cows I got.”

Annie Mackenzie:

Do you write poetry for profit and can you make a living writing cowboy poetry?

The past couple weeks have been crazy, trying to move cows, put in new water tanks in some rough country, irrigate, fix fence, haul salt, and then on top of that we had a lightning strike start a fire, setting us back another couple days. There's always something on the ranch and lately it's been a lot of somethings!

The question I would like to answer is, "Do you write poetry for profit and can you make a living writing cowboy poetry?" My poetry is something that I do for fun. It is not what pays the bills, so to speak, and in a way I'd like to keep it that way. I'd kind of hate to take the thing that brings me so much joy and turn it into a pressured job that I have to do. Sitting down to write a poem because I have to does not bring the same joy to me as writing one because it just popped up in my mind. I write when inspiration strikes. A phrase or an experience will stick out in my mind's eye along with a rhyme and then, from there, trying to create the rest of the story and put it into prose in an interesting way is a fun challenge.

I've always loved storytelling–the experience of standing around bs'ing or sitting around a campfire, I thrive off of it. I love the camaraderie, the entertainment, the smiles, and the laughter that it brings. Whether it's a shared experience or an unbelievable tale, stories can capture people's minds and hearts in a way that no other form of entertainment does. You aren't just watching, you become a part of the moment. Writing poems is my way of joining in around the campfire, so to speak. People may forget all of the stories that you share with them, but they won't forget how you made them feel when you told it.

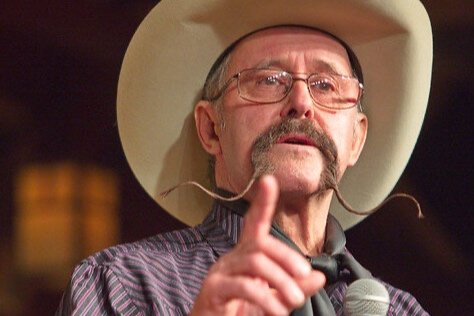

Dick Gibford:

Do you feel like the cowboy way of life is endangered?

“Do you feel like the cowboy way of life is endangered?” Answer: Yes, it is endangered and the world is moving way too fast anymore. But I would say (in answer to my own question), I am optimistic about the lifestyle of working ranch cowboys and cowgirls surviving. The beef industry needs large and small high-desert ranches of the Great Basin, and all western intermountain states, to have healthy and productive cow-calf operations. If the government doesn't interfere too much, and affordable Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management leases remain available, I think we may survive quite well, but none of us have a crystal ball. The future is what it always is–illusive. Big money schemes are always at work behind the scenes to gain more power and control over ‘we, the people.’ But more and more, I notice a trend. People in the cities want out. Folks with money want to move to the Rocky Mountain states, or Southwest, etc., to enjoy the good life on their own cattle ranch, and if they are smart they hire a native, born and raised in the area to manage it. And if they are even smarter, they will listen and learn. Myself, I love the cow camp life and the more remote the better. I am a horseman first and cowboy second. I have my own reasons for living alone out here. The peace and quiet feeds the soul daily. Call me an escapist, but it's the best way for me to live, that I have found, so I can be a more creative, enlightened human being, and I will leave it at that.

Yvonne Hollenbeck:

Here's my answer, such as it is.

The questions I am often asked are, "Where do you get your ideas?" or "How do I go about writing cowboy poetry?"

Where do you get your ideas? How do I go about writing cowboy poetry?

The two are closely related. Whenever I do workshops in schools, I first explain that cowboy poetry is poetry about anything rural. It may be about cattle, horses, cowdogs, the land, the rural lifestyle, almost anything you see looking out your window.

Having a good grasp on poetry writing, whether it be rhyming, free verse, or most any style of poetry helps, but be honest about what you write and keep it "cowboy," whether humorous or serious. Most cowboy poets are willing to help you, whether it be by critiquing your work or sharing samples and ideas. Most importantly, many gatherings and writing groups have workshops. Take every one you have an opportunity to attend. You can always learn something, no matter how many years you have been writing poetry.

DW Groethe:

Do you ever get tired of doing your own material over and over? What do you do to take a break from it?

The one question is actually a two-parter: #1...Do you ever get tired of doing your own material over and over and #2...what do you do to take a break from it?

I'm fairly fortunate as I write both poetry and songs so I have a fairly large list to choose from, but still there are a few pieces that I'd like to ease off on a bit. The problem is that invariably these are poems/songs that folks want to hear, so, by throwing in the occasional new piece I can sorta get a nice balance. When it gets down to the wire, if I've only got a short set, I'll stick with the golden oldies because it's all about the folks out front and I don't mind giving them what they want.

Ta daa,

dw

Waddie Mitchell:

Hum... what question would I like to answer that hasn't been asked?

Why? Why would an artist open themself to create images, visions, and stories that, hopefully, stir emotions?

Why? Why would a cross section of the population and of the country travel to the far outback in the middle of the winter to sit and listen to some livestock-tending, hat-wearing, unlikely poets?

Well, a few come to mind, but the one that was first is: Why? Why would an artist open themself to create images, visions, and stories that, hopefully, stir emotions?

But more importantly: Why? Why would a cross section of the population and of the country travel to the far outback in the middle of the winter to sit and listen to some livestock-tending, hat-wearing, unlikely poets?

When I first got interested in writing poems, I read that poetry is "word music." For a long time my answer to those questions would be: Word music, so pleasing to the ear, so refreshing to the mind, such primal enjoyment.” Over the years, though, my ideas changed to: It's all about the story. The story that's embedded within us. The story that is part of our very nature, as sure as music, as needed as companionship. The story and the listener. The story of the cave dwellers thousands and thousands of years ago telling of the dangerous hunt. The story that tickles or wounds. The story that educated the uneducated and the story that makes a difference.

Through the years, the stories have changed but this need for story inside people is functional and has not yet gone the way of the appendix. To the first question (why would an artist do it?), my answer is: Because that's what artists do. To the second (why do people come?), my answer is: People come for the honesty, the art, the social aspects of it, the learning, the shopping, and the friendships old and new…and that is all just one attendee.

So, yesterday, the answer to the question would have been, "A story in word music recited by a person of the land is why people like it and come all that way to celebrate the whole lifestyle.” That last sentence, though, reminded me that there might be a few other things–great music and musicians, workshops, dancing, gambling, eating till you founder, and partying all night might have a little part in luring the audiences–so I guess we've come full circle back to my answer to "Why do they come?" OK, here goes. My answer today is: “They come because of and for the cowboy poet, plain and simple (take that, you crooners of the range).”