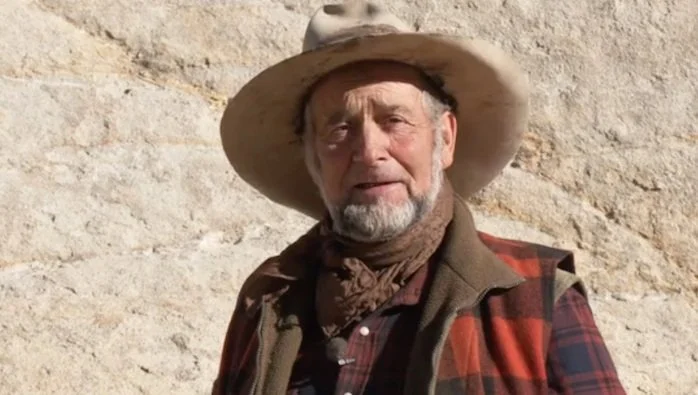

Each year, the Western Folklife Center invites artists to the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering. Unfortunately for all of us, the Gathering is only a week long, hardly enough time to get to know all the artists. Through this blog, we hope to give you a closer look at some of the artists. To start things off, Gathering Manager, Tamara Kubacki, interviewed Andy Wilkinson and Andy Hedges. As part of the interview, Andy Hedges sent along two tracks from their upcoming album, The Outlands. Get an exclusive first listen here!

LISTEN to The Crooked Trail

[audio http://westernfolklifecenter.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/02-the-crooked-trail-by-andy-wilkinson-and-andy-hedges1.mp3]

TK: You have a new website, andyandandy.com. After three albums, does this mean that yours is a permanent partnership?

AH: We’ve also just finished recording a fourth album that will be released by the end of the year. I don’t foresee us ending the partnership but I am sure that we’ll both continue to do solo projects and perform solo at times. One of the nice things about our arrangement is that there is no pressure and no expectations. There was never a formal beginning. We just sort of fell into working together and I’d like to think that if it ever ends, it would be the same way.

AW: Exactly. There are two other important factors to consider. First, we’ve never come up with a cool band name. Second, at my age a permanent partnership really doesn’t mean much!

TK: You also released a new CD this year, Mining the Motherlode. Many of the reviews I’ve read point out that much of the subject matter is the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. Andy Wilkinson said, in a review by Margo Metagrano, “The history of the American West was openness. The future of the American West is water. Mining the Motherlode explores that future by using the lens of art to look at our present and our immediate past." Will you expand on the idea of using art to look at the present and immediate past?

AW: The principal business of art is storytelling. And the principal business of storytelling is to give us an understanding of the world that is distinctly human. The historian sees their view, even though it is ever-changing, to be the objective truth. The artist knows that the ever-changing nature of truth can only be captured in a story.

TK: What about using history to explore the present and future? A lot of the songs you perform, not just on the newest CD, are arrangements of traditional and folk songs. How are traditional songs relevant to today’s listeners?

AH: Traditional American folk songs are weird, strange, funny, scary, sad, and intriguing stories about the human condition. Bob Dylan said a person could learn how to live listening to folk songs. And all American music comes from this, whether it’s rock-n-roll, country music, blues, or cowboy songs. It all grows out of this same tree of American folk music and it is as relevant now as ever, especially in a time when it’s hard to find anything that’s real. These traditional songs are honest. With that said, I don’t approach the music as a traditionalist or a purist. I am not trying to duplicate the sound of a 1930s recording. I am simply an interpreter, trying to bring what I have to the songs and looking for ways to change them – new verses, new melodies, combining songs, anything that makes the songs fit. It’s all part of the folk process.

TK: Your collaboration is rich with dichotomies that prove that opposites attract. Your voices are very different from each others’: Andy Wilkinson writes original material while Andy Hedges arranges the traditional songs; the topics you explore cover both history and the future; and Andy Wilkinson is a bit older than Andy Hedges (sorry for pointing out your ages!). I find it interesting that all of these opposing ideas work so well together. How do you do it?

AH: I’ll add another one: Wilkinson is a poet and I am a reciter. But, we do have the same name! I think it’s the differences that make our collaboration work. It would be boring if we were both the same age and both songwriters.

AW: I’ll add only this: our souls are the same age.

TK: Speaking of your ages, people might assume that because Andy Wilkinson is older, he is a mentor to Andy Hedges. But as I've gotten to know you, it seems to me that you are truly friends and that your musical relationship is a partnership rather than a teacher/student situation. Is Andy Wilkinson a mentor or more?

AH: I don’t really think about or notice the difference in our ages. I’ve always been friends with folks who were much older than myself. Andy Wilkinson IS a mentor to me but he’s much more than that. Or maybe he is exactly what a mentor should be: a friend who is generous with their time, talent, and knowledge, who treats you as an equal and is also eager to learn from you.

AW: I should add that I learn every bit as much from Andy Hedges as I hope he learns from me.

TK: I am also interested in Andy Hedges’ attraction to traditional and older styles of music. Where do you find the songs you rearrange? How does working with Andy Wilkinson help your process?

AH: I immerse myself in all types of old time and American folk music. I have a special interest in cowboy songs but I listen to a little bit of everything and it’s all connected. I listen to old 78s and LPs and I buy lots of CDs and I download music. I collect old folk songbooks and I’m always keeping my ears pricked for something that I can use. Sometimes Wilkinson writes a song that will remind me of something I’ve heard or will send me in search of a certain kind of song to pair with it. For example, Mining the Motherlode originally started with Wilkinson writing a little bunch of songs for a program we did about the “next Dust Bowl” and we wanted to include some depression era songs and some Dust Bowl songs so I began digging deeper into that material.

TK: Andy Wilkinson, you also seem to be interested in historical figures and are presenting your show Charlie Goodnight: His Life in Poetry and Song” at the Gathering this year. Can you speak to writing original material, especially music, that draws on history, and how Andy Hedges’ traditional sensibilities affect your current work?

AW: I am fond of saying that I write from history because I’m lazy; there are no better characters, no better plots, no better stories than what can be found in the real world, and if it’s already happened, it’s history. So in that, I am already a traditionalist. Besides which, good songs are timeless — no song speaks to me just because it’s old, or just because it’s new, or just because it comes from some particular tradition or genre.

TK: A lot of your music not only illustrates a time in history, but also evokes a sense of place. What role does living in Texas play in the music you create?

AW: I don’t think living in Texas makes any difference. I do think that living in this particular part of Texas plays an enormous role. Out on the Southern Plains, we’re still very close to a history that’s particular to this place. Cities tend to develop in many of the same ways, but each countryside seems — at least, to me — to have its own, unique history.

TK: On your latest release, Andy Hedges’ wife, Alissa, and Andy Wilkinson’s daughter, Emily Arellano, play a more noticeable and prominent role, each of them singing lead on two songs: “Dust Can’t Kill Me” (Emily) and “Old-Timey Heart” (Alissa). Both of them have beautiful voices that complement your voices in different ways. Why have you decided to include them in your collaboration, and how has it enhanced the recording?

AH: For one, they are much better to look at than the two Andys! And, as you have pointed out, they have beautiful voices that complement what we are already doing. They also allow us to perform some songs like “Old-Timey Heart” that would not make sense with a male voice. The thing I really like about performing with Alissa, Emily, and Andy is that we are all friends and family. When we make a record, we record almost everything in real time with very few overdubs and we don’t use any session players. Everything you hear on the new record comes from the four of us. It’s a very natural way to make music.

AW: And I’ll add that my son, Ian, is playing harmonica on our newest and as-yet-unreleased project. I can’t imagine doing something as important as art with people other than family and friends. We’re very, very lucky.

LISTEN to The Old Chisholm Trail

[audio http://westernfolklifecenter.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/03-the-old-chisholm-trail-by-andy-wilkinson-and-andy-hedges1.mp3]

TK: Thank you for taking the time to answer my questions. Readers who want to know more about Andy Wilkinson and Andy Hedges can visit their website at andyandandy.com, or, better yet, talk to them in person at the 28th National Cowboy Poetry Gathering, January 30 – February 4, 2012.

![4599341765_3f4b218b7c_m[2]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56972f85b20943f1333a2f06/1469421726508-L6R1UA8E1SA286IKFPDK/4599341765_3f4b218b7c_m2.jpg)