Got a Question? Ask A COWBOY POET!

April 2024

What sensory ingredients do cowboy poets mix together to make a poem? Do they add a pinch of sound and a heap of imagery, or vice versa? This month, the cowboy poets talk about their recipes for writing poetry from scratch as they answer this question:

“How much do you think about the sound/music versus the imagery of your poem?”

~ @carteagraphy

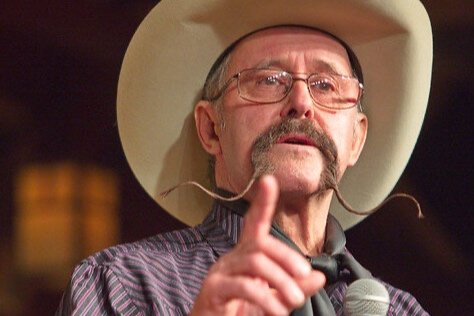

Dick gibford:

Sound and music from nature are a big part of my poems. A poem should paint a visual picture, but sounds are just as important. I can’t think of many cowboy poems that sound does not enter into. Kiskaddon comes to mind: “And the only other sound was the creaking of the saddle and the hoofbeats on the ground.” From my poem “The Sound of Spurs:” “The sound of rushing water and long grass combed by the wind, the sighing of the pines on the mountain side, reminds me of dear ol’ friends.” These are all natural sounds from nature that we cowboys and ranch folks hear every day.

Many of Mother Nature's sounds are musical: the mockingbird, of which we have a lot of them in this part of California, comes to mind. Many a morning I sit and listen to this talented bird who memorizes almost all the other bird songs around here! There is one right now. I can see him sittin’ on a juniper limb not more than a hundred feet from camp, happily singing away! As far as music itself, the guitar comes to mind first as the old western standard to enhance the feeling in any cowboy poem. The cowboy way of life does not have much money attached to it, but it's rich in romance and spiritual feeling. The beautiful sounds from nature and music are a big part of it all.

Whoever this dear person may be asking this question, I want to thank them very much. It gave my beat-up old cowboy carcass a nice break from a job that, try as I might, I cannot find one ounce of romance involved in the doing…shoeing a horse!

yvonne hollenbeck:

When writing a poem, I do not give much thought to the sound/music versus the imagery of my poem. I write standard cowboy poetry, i.e. rhyme and meter style, and not just by trying to have a good rhyming pattern do I find myself tapping my toe to my lines. I have a strong musical background where I learned to play by ear at an early age, chording to my champion-fiddling dad, and I was taught strict meter through that genre. I guess that is where I seem to subconsciously write poetry with a rhythmic pattern. A number of my poems have been set to music by various artists, which I presume due to the imagery of those poems.

waddie mitchell:

Interesting question. All elements of a poem are important, just as cement, bricks, and level are all essential to a good brick wall. Imagery is important. One attempts to transport the reader or listener to the idea or story. Idea and story are important, but in my experience the tune (meter) is probably what is the most important to me. Without a tune, it's easy to have too many syllables in one line and then too few in another. Our kind of verse is best recited.

We have through history been given many wonderful examples of appropriate tunes, if you will, for the type of idea we write about. Most times a boogie-woogie tune isn't the best choice for a tragic story. When done right, the listener, like with a good song, is mesmerized as much by the tune as the verse or lyrics. In poetry there are always exceptions. Think of the songs you remember from long ago. If you consciously look for those things, you will get an idea of what I'm talking about. It's generally as much about the tune as it is the lyric, we just don't think about it. Too often, a poet will get stuck in one tune, which I feel is a mistake. Sometimes a great idea or story will be partly lost or unappreciated if the tune or meter doesn't enhance the takeaway. To my way of thinking, story, tune, and imagery are all must haves, but I feel the meter is the milk in your sausage gravy. It brings it all together.

dw groethe:

Maybe because I'm a musician, this is an easy answer for me. Whether it's a poem or a song I'm working on, it's all of a piece. It's like it's all happening at once, and I make most of the changes at the time I'm writing. When the piece has been basically finished (which could be anywhere from five minutes to five hours), I set it aside for a little think time, and eventually I'll come back to it for a final polish.

So, for me, it all comes together at once, no matter what the poem or song is about.

Hope that helps and thanks for asking.

bill lowman:

I'm a bit astray on the question, not that it isn't a good one (it's more apt to be me). If I'm following your question, my rhythm of recording a new poem comes spontaneously, unforced, and very quickly. I do not labor over a poem’s construction. They flow freely, so fast at times it's difficult to jot a verse down on my shirt pocket notebook before the next one crowds out my thoughts. My editing and rhythmic flow comes originally as I continue to recite it in my mind.

Years ago Wally McRae once told me, "You have to hum it in your mind to accomplish correct meter."

That's good enough for me. I'm most interested in recording a current event that will become history tomorrow.

annie mackenzie:

I write my poetry very much by ear. Many of them are written as a song, and then I deliver them as poems—mostly due to the fact that I'm a poor cowpuncher who can't even afford a bucket that could carry a tune. Even so, I like to write them aloud so that I can hear how the words flow together, listening for the lines that need to be adjusted to fit the cadence that I'm going for. I don't know any way to describe it, other than I try to write the stanzas so they will strike my ear in a pleasing manner, and I hope that others find it pleasing as well. I do also think about the imagery of my poems. However, if a line paints a beautiful picture but doesn't fit the sound, I will leave it behind unwillingly, after much whining to my sister who I've begged to help make it work, and several attempts to rewrite it, but eventually the ear wins over the eye.